The Cancer Learns

Recent findings bring Technion scientists to propose a new framework for cancer research. At its heart is the apparent capacity of cancer cells to learn and adapt

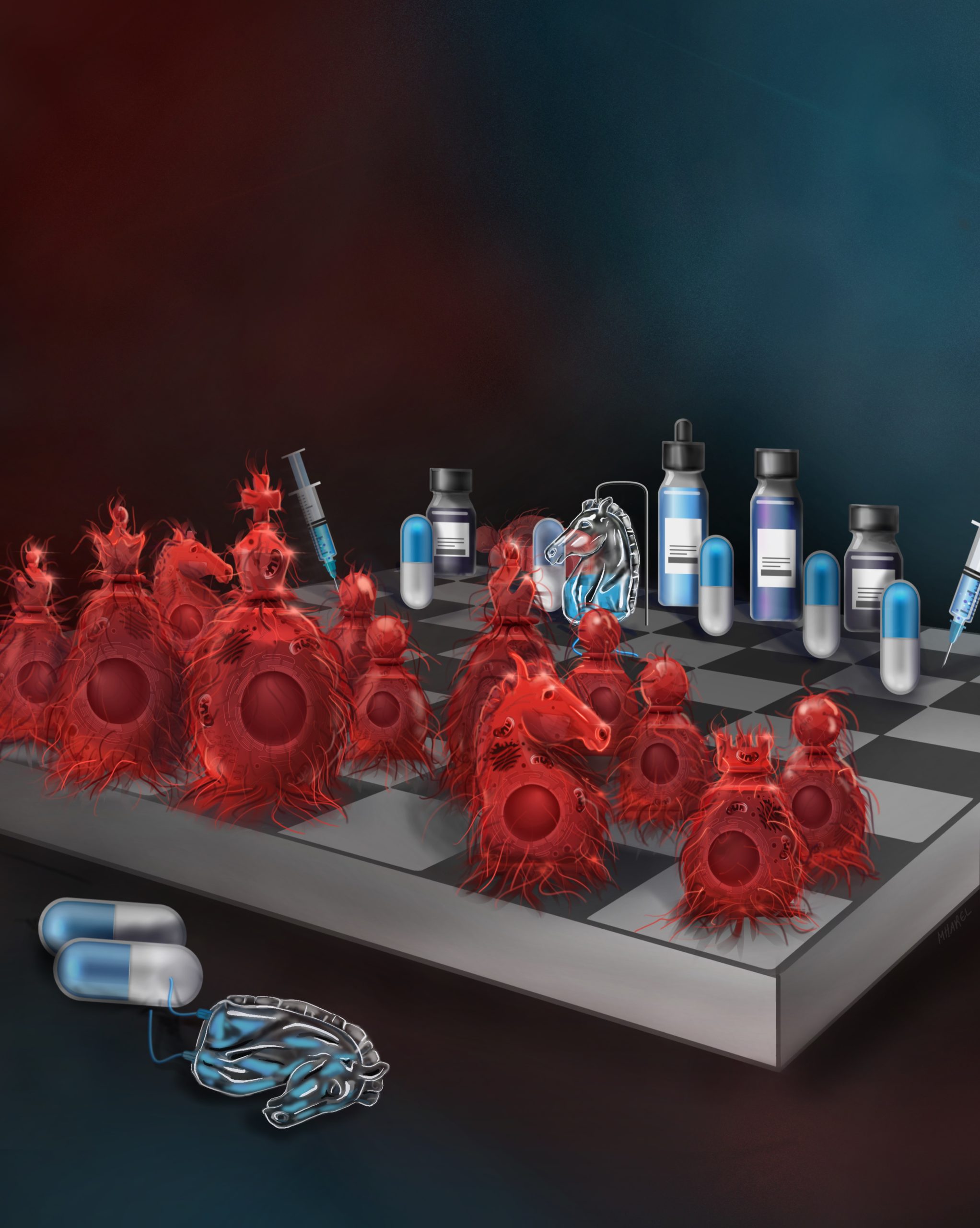

What enables cancer to metastasize – to spread to different parts of the body, with their different environments and grow there? How do tumors become resistant to drugs? In an opinion piece recently published in iScience, Technion researchers Aseel Shomar, Professor Omri Barak, and Professor Naama Brenner propose a novel explanation, in the hope that better understanding should lead to better treatment. The three propose that cancer cells are able to learn and adapt to changing environments, through actively searching for solutions that would enable them to survive. They suggest that studying cancer with the approach and tools of learning theory will advance our understanding of these phenomena.

It is commonly thought that both drug resistance and the ability to metastasize appear in cancer cells as random mutations. Since such a mutation is advantageous to cancer cells, enabling them to survive in an environment that attempts to fight them, these mutations become dominant. However, mounting evidence from research groups around the world do not seem to match this hypothesis, and treatment plans based on it did not significantly increase patients’ life expectancy. Now, Aseel Shomar, Prof. Barak, and Prof. Brenner propose a new hypothesis that matches the evidence at hand: cancer cells learn and adapt to their environment, enabling them to develop drug resistances and conform to the new environments of metastasis locations.

A cell has no brain, so how does it learn? Sensing stress, Prof. Brenner explains, the cell seeks to reduce that stress. It embarks on a trial-and-error process within the gene regulatory network, changing the way existing genes are expressed. An interaction that reduces the stress gets strengthened. Even so, considering the number of possible configurations the cell can try, it can seem unlikely that the process would work. However, using computer simulations based on learning theory, the group showed that cells could in fact learn and adapt in this fashion. One element of what makes this feasible is that more than one solution may be found to solve the same problem the cell faces. Another element is the way the gene regulatory network is structured, with regulatory “hubs” that control parts of it.

Cancer cells are not unique in their learning ability. Previous studies by Prof. Brenner, Prof. Erez Braun, and others have shown that yeast cells can adapt to new environments and develop abilities they did not initially possess. Few other labs around the world have demonstrated this effect in simple organisms. Learning theory provides the framework and the mathematical tools to study these phenomena. The Technion’s Network Biology Research Lab aims to explore the way various biological systems adapt – a process that is not fully understood. The Lab’s researchers, coming from varied faculties including Physics, Electrical & Computer Engineering, Chemical Engineering, and Medicine, work on connecting the evolving theoretical models to complex and dynamic biological systems.

While tumors that learn and adapt might sound like a nightmare, Aseel Shomar, Prof. Barak, and Prof. Brenner also found reason for hope. There is perhaps a key to the problems cancer continues to pose. While the capacity for learning is there in the cells, normally something holds it back. In fact, the same mutations found to promote cancer in our body, can be carried by cells that still remain healthy. Even cells from active tumors, transported into healthy tissue, were in some experiments “cured,” reverting to their non-cancerous state.

“There is an interaction between the individual cell and the tissue,” Prof. Brenner explains. “The cell has the capacity to explore, but the tissue imposes order and stability. We propose that using the approach and methods of learning theory will help investigate this interaction in greater depth. Cancer could perhaps be treated through strengthening the tissue’s ability to calm and control the pre-cancerous cell.” A better understanding of the system, such as the three provide, is a crucial step towards developing more effective treatments.

Most scientific studies add a titbit of data to an existing framework. This is one of a rare category of studies that re-examine existing data and propose a novel framework, offering answers to questions that had hitherto remained unanswered, and opening up new avenues of exploration.

The study was led by Ph.D. student Aseel Shomar, under the joint supervision of Profs. Omri Barak and Naama Brenner. It was supported by the Israeli Science Foundation (ISF) and the Adams Fellowship Program of the Israel Academy of Science and Humanities.

For the full article in iScience click here