As told by ATS Supporter Norman J. Rosenberg

A few years after Israel’s founding, a debate erupted in the Knesset over how to feed its growing population. The country was relying heavily on U.S. donations of surplus grains and dairy products. Some said the country needed to rely less on others and more on its own technological prowess. As one lawmaker declared, “We don’t need powdered milk, we need Lowdermilk.” He was referring to the renowned American conservationist Walter Clay Lowdermilk, the subject of a fascinating book written by Technion supporter Norman J. Rosenberg.

Lowdermilk, not Powdered Milk!: An American conservationist’s unlikely role in Israel’s creation and early development tells the story of Lowdermilk’s pioneering work in water and soil resources, weaving in episodes of Mr. Rosenberg’s own overlapping career in Israel. Mr. Rosenberg is donating proceeds to the Technion, where Lowdermilk helped launch the agricultural engineering department in 1953. “I knew many faculty members, and know Technion students are diligent, hard workers,” he recently recalled. “I think it’s important that an institution like the Technion, which is doing so much in high-tech, continues to contribute solutions to the world’s worsening environmental problems.”

Lowdermilk was Assistant Chief of the U.S. Soil Conservation Service in 1938 during the Dust Bowl years, a period when severe dust storms damaged America’s plains and prairies. On assignment for the Secretary of Agriculture, he loaded his Buick with suitcases, typewriters, cameras, and other supplies for a 20,000-mile, 18-month journey through North Africa and the Middle East to study how a once fertile region had become barren and unproductive. With his wife, two children, niece, and secretary, he visited ancient and modern sites, observing the deforestation, overgrazing, eroded soils, and low productivity typical of the region.

The group crossed the Sinai into Palestine in early 1939. Observing the progress made by Jewish settlers in reclaiming the devastated landscape, Lowdermilk debunked the British White Paper of 1939 that restricted Jewish immigration on the grounds that Palestine lacked the natural resources to support a larger population. His findings influenced the United Nations partition plan, which led to the establishment of the State of Israel, and his book Palestine: Land of Promise outlined a water development scheme that was partially adopted by the National Water Carrier.

Like Lowdermilk, Norman Rosenberg is a soil scientist and advocate for Israel. Soon their worlds would intersect.

Mr. Rosenberg was raised in Brooklyn. He and his future wife, Sarah, were members of a Zionist youth group. In his late teens Norman decided to move to Palestine. Breaking the news to his parents, they offered some sound advice: “‘Go to agricultural school, so when you get there you can do something useful,’” recalled Mr. Rosenberg.

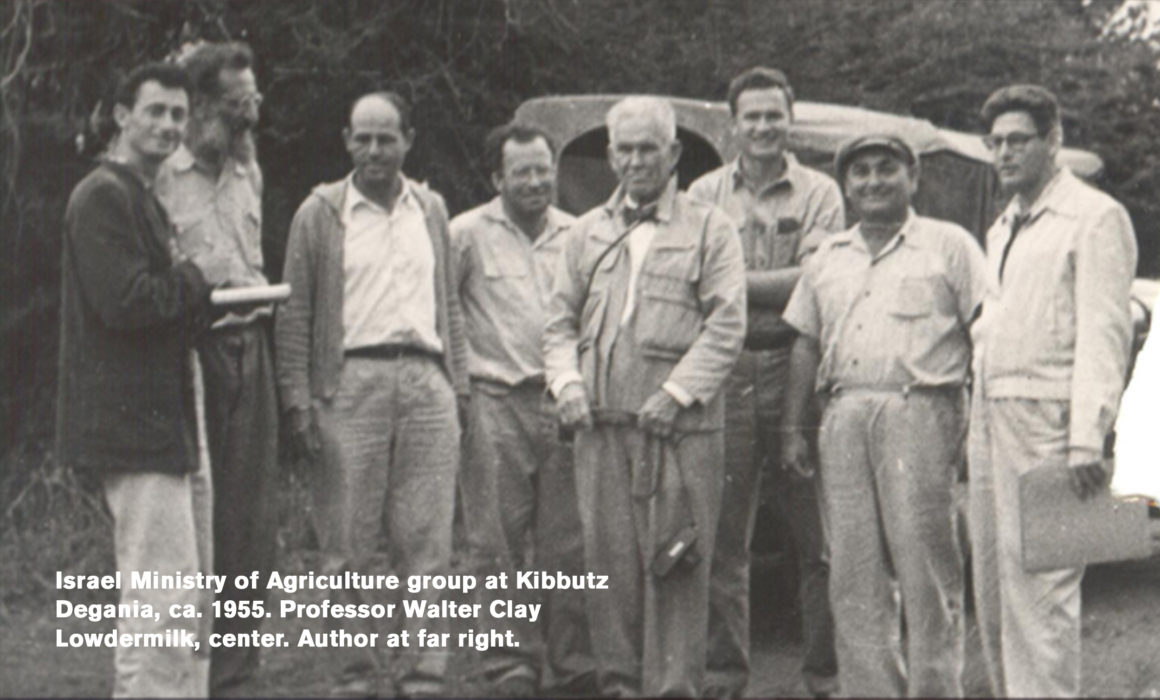

On graduation from Michigan State University in 1952, Sarah and Norman, now married, made the move. It was just about then that Lowdermilk had returned to Israel to help establish the Israel Soil Conservation Service. “I had studied soil conservation, so they were very happy to hire me,” remembered Mr. Rosenberg. “I became part of a small group of men that conducted a soil survey of the entire country. Lowdermilk conceived of the survey. That’s how I got to know him.”

The Rosenbergs and Lowdermilks lived just a mile apart in Haifa during the Sinai War in 1956. “We were told by the U.S. Consulate to evacuate, but both families stayed on,” Mr. Rosenberg recalled. Like thousands of other residents, they watched the Israeli Navy tow into port the captured Egyptian destroyer that had shelled Haifa the night before.

Lowdermilk devoted the latter part of his 1951-1957 stay in Israel to establish agricultural studies at the Technion. He helped plan the academic curriculum, raised funds to construct a building, and served as the school’s first dean. In turn, the Technion honored him by naming the new department the Lowdermilk School of Agricultural Engineering. Today, agricultural studies is part of the Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Mr. Rosenberg, meanwhile, returned to the U.S. in 1957, earned his master’s degree at Oklahoma State University and his doctorate at Rutgers University, and then became a professor at the University of Nebraska. “Although I never crossed paths with Dr. Lowdermilk again after the fifties, I remember him as very polite and avuncular, a wonderful mentor and genteel person,” he said.

Anxious to see Israel again, Mr. Rosenberg spent a sabbatical in 1968 helping the Technion Lowdermilk School start a program in agricultural meteorology. As chance would have it, he shared an office in a tower built for Lowdermilk’s personal research on soil erosion. There he learned how Lowdermilk set an informal tone for the department, encouraging students to challenge his views, and inviting faculty and students alike to his home.

The Rosenbergs got involved with the American Technion Society (ATS) when they moved to Washington, D.C. in the 1980s. Then in 2016, after retiring to California, Mr. Rosenberg was speaking about Israel and soil conservation at his son’s synagogue when he was surprised to learn: “no one in the room, not the youngest to the oldest, had heard of Lowdermilk.” Soon after, an ATS fundraiser put him in touch with water expert and Technion supporter Seth Siegel. Mr. Siegel introduced him to Lowdermilk’s daughter, who at the age of 10 had traveled with her family on the historic fact-finding journey. She provided access to her father’s files, interviews, and photos. Rosenberg’s book was published in 2019 and is available on Amazon.

Royalties for Lowdermilk: Not Powdered Milk! will be donated to the Technion to support new and ongoing research on water resources, grassland conservation, and soil erosion control. “Like so much of the developed world, exploitation of soil and water resources has stressed Israel’s environment and the ecosystems that are so important to the well-being of the populace,” said Mr. Rosenberg. “So beautiful a land as Israel needs the attention of the highly trained and devoted scientists and engineers that the Technion produces.”